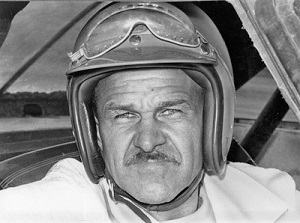

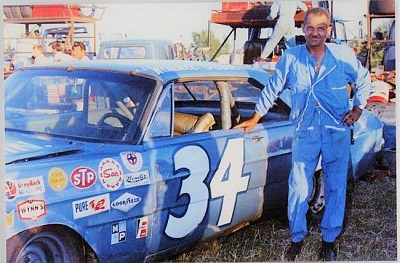

WENDELL OLIVER SCOTT - 08/29/1921 - 12/23/1990

was an American stock car racing driver from Danville, Virginia. He is the only black driver to win a race in what is now the Cup Series. According to a 2008 biography of Scott, he broke the color barrier in Southern stock car racing on May 23, 1952, at the Danville Fairgrounds Speedway. Scott's career was repeatedly affected by racial prejudice and problems with top-level NASCAR officials. However, his determined struggle as an underdog won him thousands of white fans and many friends and admirers among his fellow racers. Scott was around thirty years old when he was sitting in the bleachers of local speedways, watching white men race. Up to then, he had lived his whole life under the rigid rules of segregation. The Danville races were run by the Dixie Circuit, one of several regional racing organizations that competed with NASCAR during that era. Danville's events

always made less money than the Dixie Circuit's races at other tracks. "We were a tobacco and textile town -- people didn't have the money to spend," said Aubrey Ferrell, one of the organizers. The officials decided they would try an unusual, and unprecedented, promotional gimmick: They would recruit a Negro driver to compete against the "good ol' boys." To their credit, they wanted a fast black driver, not just a fall guy to look foolish. They asked the Danville police who the best Negro driver in town was. The police recommended the moonshine runner whom they had chased many times and caught only once. Scott brought one of his whiskey-running cars to the next race, and Southern stock car racing gained its first black driver. (Scott's debut often has been reported as taking place in the 1940s, but articles in two Danville newspapers, the Register and the Commercial Appeal, confirm the date

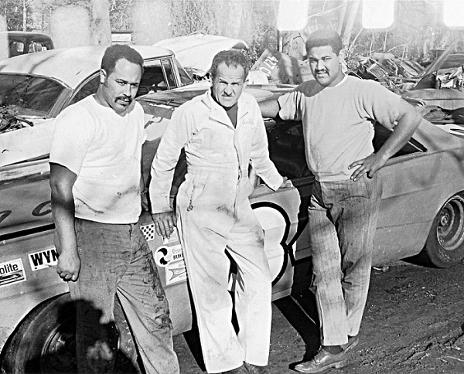

as May 23, 1952.) Some spectators booed him, and his car broke down during the race. But Scott realized immediately that he wanted a career as a driver. "Right from the first, I loved driving that car in that race.". The next day, however, brought the first of many episodes of discrimination that would plague his racing career. Scott repaired his car and towed it to a NASCAR-sanctioned race in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. But the NASCAR officials refused to let him compete. Black drivers were not allowed, they said. This occurred many times with NASCAR sanctioned events. He ran as many as five events a week, mostly at Virginia tracks. Some spectators would shout racial slurs, but many others began rooting for him. Some prejudiced drivers would wreck him deliberately. Many other drivers, however, came to respect Scott. They saw

his skills as a mechanic and driver, and they liked his quiet, uncomplaining manner. They saw him as someone similar to themselves, another hard-working blue-collar guy swept up in the adrenalin rush of racing, not somebody trying to make a racial point. Scott understood, though, that to rise in the sport, he somehow had to gain admission to the all-white ranks of NASCAR. He did not know NASCAR's celebrated founder and president, Bill France, who ran the organization like a czar. Instead, Scott found a way, essentially, to slip into NASCAR through a side door, without the knowledge or consent of anyone at NASCAR's Daytona Beach headquarters. He towed his race car to a local NASCAR event at the old Richmond Speedway, a quarter-mile dirt oval, and asked the steward, Mike Poston, to grant him a NASCAR license. Poston approved Scott's

license. He asked Scott if he knew what he was getting into. "I told him we've never had any black drivers, and you're going to be knocked around," Poston said. "He said, 'I can take it.' Later he confided to Scott that officials at NASCAR headquarters had not been pleased with his decision. "He told me that when they found out at Daytona Beach that he had signed me up, they raised hell with him," Scott said. Scott met Bill France for the first time in April 1954. The night before, Scott said, the promoter at a NASCAR event in Raleigh, North Carolina, had given gas money to all of the white drivers who came to the track but refused to pay Scott anything. Scott said he approached France in the pits at the Lynchburg Speedway and told him what had happened. Even though France and the Raleigh promoter were friends, Scott said France immediately pulled some money out of his pocket and assured Scott that NASCAR would never treat him with prejudice. "He let me know my color didn't have anything

to do with anything," Scott said. "He said, 'You're a NASCAR member, and as of now you will always be treated as a NASCAR member.' And instead of giving me fifteen dollars, he reached in his pocket and gave me thirty dollars." Scott won dozens of races during his nine years in regional-level competition. His driving talent, his skill as a mechanic and his hard work earned him the admiration of thousands of white fans and many of his fellow racers, despite the racial prejudice that was widespread during the 1950s. In 1959 he won two championships. NASCAR awarded him the championship title for drivers of sportsman-class stock cars in the state of Virginia, and he also won the track championship in the sportsman class at Richmond's Southside Speedway. In 1961, he moved up to the Cup series. In the 1963 season, he finished 15th in points, and on December 1 of that year, driving a Chevrolet

1970 Torino

1972 Charlotte

Bel Air purchased from Ned Jarrett, he won a race on the one-mile dirt track at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida -- the first CUP event won by an African-American. Scott passed Richard Petty, who was driving an ailing car, with 25 laps remaining for the win. Scott was not announced as the winner of the race at the time, presumably due to the racist culture of the time. Buck Baker, the second-place driver, was initially declared the winner, but race officials discovered two hours later that Scott had not only won, but was two laps in front of the rest of the field. NASCAR awarded Scott the win two years

later, but his family never actually received the trophy he had earned till 2010--37 years after the race, and 20 years after Scott had died. He continued to be a competitive driver despite his low-budget operation through the rest of the 1960s. In 1964, Scott finished 12th in points despite missing several races. Over the next five years, Scott consistently finished in the top ten in the point standings. He finished 11th in points in 1965, was a career-high 6th in 1966. Scott was forced to retire due to injuries from a racing accident at Talladega, Alabama in 1973. He achieved one win and 147 top ten finishes in 495 career Grand National starts. Scott died on December 23, 1990 in Danville, Virginia, having suffered from spinal cancer. The film Greased Lightning, starring Richard Pryor as Scott, was loosely based on Scott's biography. In April 2012, Scott was nominated for inclusion in the NASCAR Hall of Fame. Some info from Wikipedia

Wendell's Son receives 1963 Winners Trophy 2021

All Photos copyright and are property of their respective owners